- Would you be my neighbor?

- Six Running Back Archetypes, revisited

- Backwards Matching: Moving from Old to Young

- Forward Matching: Young to Old

- CHAPTER SUMMARY

Would you be my neighbor?

Last time, we talked about some of the things we can learn from run distributions. There were essentially no stats involved – we relied on our own instincts and natural pattern recognition to explore different ways in which running backs can be successful in the NFL, using data visualizations alone. Some (like McCoy) are successful because they have wiggle, others (like Law Firm) are successful because they don’t. Many (like Frank Gore), found their value by grinding out respectable yards at a high volume, while a select few (like Woodhead) could exploit their limited usage to fullest extent by keeping defenses guessing with their dual threat skills. And finally, a sizeable number of running backs are only notable by their inability to do any of this well (see: Alfred Blue, Trent Richardson).

But considering the goals of the project, we thought it would be interesting to address the same question – “Which players appear to produce similar output?” – using a completely different approach.

Today, we will be using algorithms instead of instinct to find comparable players.

“Think about what we were actually doing last time around. We were finding groups of players whose run distributions were different from the average but similar to one another. “Different” and “similar” was mostly defined by how closely the cumulative density curves were aligned. That’s something you can eyeball, but it’s also something you can measure. For this chapter, we wrote an algorithm that finds the space between each player’s run distribution and ranks them from least space (most similar) to most space (least similar).”

“Think about what we were actually doing last time around. We were finding groups of players whose run distributions were different from the average but similar to one another. “Different” and “similar” was mostly defined by how closely the cumulative density curves were aligned. That’s something you can eyeball, but it’s also something you can measure. For this chapter, we wrote an algorithm that finds the space between each player’s run distribution and ranks them from least space (most similar) to most space (least similar).”

Actually, we used a bit of a trick here. Remember that yardages in the official scorekeeping books are rounded to whole yards. That means that finding the difference between two “curves” is actually identical to finding the difference between the area of each of these rectangles:

“But we can do even better than that. Notice how each of those rectangles between the two players has exactly the same width: one yard. That means if we know the height of each rectangle (e.g. 0.05, or a 5% difference in the cumulative density curves), we also know the area. Minimizing the “area” between these two “curves” is mathematically equivalent to minimizing the distance between the individual distances at each of the discrete yardages (i.e. the “heights” of all the rectangles).”

“But we can do even better than that. Notice how each of those rectangles between the two players has exactly the same width: one yard. That means if we know the height of each rectangle (e.g. 0.05, or a 5% difference in the cumulative density curves), we also know the area. Minimizing the “area” between these two “curves” is mathematically equivalent to minimizing the distance between the individual distances at each of the discrete yardages (i.e. the “heights” of all the rectangles).”

Doing it this way completely avoids the need for calculus, which is typically how people do “area under the curve” type calculations. All we need is simple addition and subtraction: find the difference between the players at each yardage (e.g. how far apart at 0 yards? How far apart at 1 yard? How far apart at 2 yards? etc.), then add up those differences.

Of course, this would be ludicrous do by hand for every possible combination of players. Luckily, computers are very good at doing simple, repetitive things simply and repeatedly. So we’re just going to give the computer the run distributions for each player, then compare every player to every other player and calculate the difference using the adding and subtracting method we described above (you can play with the app yourself and read more about the method here). Easy!

“Congratulations, we’ve just reinvented Nearest Neighbor algorithms!”

“Congratulations, we’ve just reinvented Nearest Neighbor algorithms!”

Basically, yeah. Specifically, we’re doing something conceptually similar to Nearest Neighbor Retrieval. We give the algorithm some set of measures, in this case the proportion of runs that make it to different yardages, and the algorithm maps out how close the players are to one another along the totality of those measures – it finds the “nearest neighbors.” Then we can “query” a specific player, and find (or “retrieve”) the closest matches.

“This is actually a pretty unorthodox use of these techniques. It’s much more common to use nearest neighbor algorithms for classification. For example, let’s say we didn’t know whether some guy was a traditional running back or a fullback. We can give that mystery player’s distribution to the algorithm, and it might tell us that 9 out of the 10 nearest neighbors were fullbacks. The algorithm would then “vote” with a 9:1 ratio that the mystery player was a fullback. We’re not doing this extra classification step – we’re simply seeing if we can find anything interesting by just looking at the “nearest neighbors” for particular running backs directly, to keep things simple.”

“This is actually a pretty unorthodox use of these techniques. It’s much more common to use nearest neighbor algorithms for classification. For example, let’s say we didn’t know whether some guy was a traditional running back or a fullback. We can give that mystery player’s distribution to the algorithm, and it might tell us that 9 out of the 10 nearest neighbors were fullbacks. The algorithm would then “vote” with a 9:1 ratio that the mystery player was a fullback. We’re not doing this extra classification step – we’re simply seeing if we can find anything interesting by just looking at the “nearest neighbors” for particular running backs directly, to keep things simple.”

I prefer “creative use.” We’re just thinking outside of the box here!

I should mention though, that players with small samples tend to have really noisy curves, so we’re restricting this process to only players with at least 50 carries over the past six years. That leaves us with 187 players to compare to one another.

There’s also a few important things to keep in mind. First, we only have data from 2010 on. A number of players in the data set - say, LaDainian Tomlinson, Adrian Peterson, Steven Jackson etc. - have whole seasons of their careers missing. So if you see LaDainian or SJax pop up in a match, keep in mind that it’s only comparing production after 2010. So we’re not comparing new players to LaDainian Tomlinson per se, we’re comparing new players to late career LaDainian Tomlinson. We could leave out players that started before 2010, so we’d have full data sets for everybody, but that would require omitting most of the really important running backs of this decade, including Gore, Charles, AP, and Fred Jackson. So we decided to leave them in - just remember the context.

Second, remember that a running back’s rushing production here depends on a lot more than just their skill. Because this is a retrospective analysis, we’re not trying to distinguish running backs from their offensive lines, quarterbacks, and playcalls. We’re not trying to project anything to new circumstances, we’re trying to understand how running backs produced in the six years between 2010 and 2015. As such, the production for each player can be thought of as being influenced by both the running back and their situation.

But enough background. Let’s take this for a test drive!

Six Running Back Archetypes, revisited

Last time, we eyeballed our way to six running back archetypes, and listed a couple of guys who really seemed to fit the bill for each. If we did a good job (and if our algorithm is worth a damn), we should see those same players pop up as matches. I’d be thrilled if my listed archetypes from last time made an appearance within the top 10 of one another’s matches in this automated procedures.

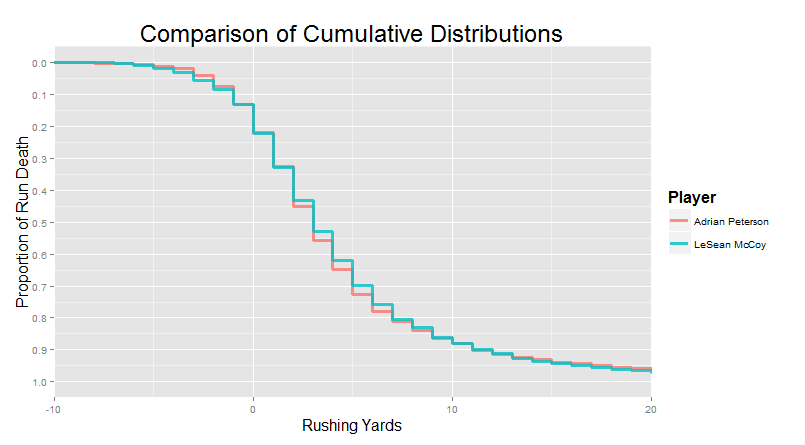

For my home-run hitters, I listed LeSean McCoy, Adrian Peterson, Justin Forsett, Reggie Bush, and Christine Michael.

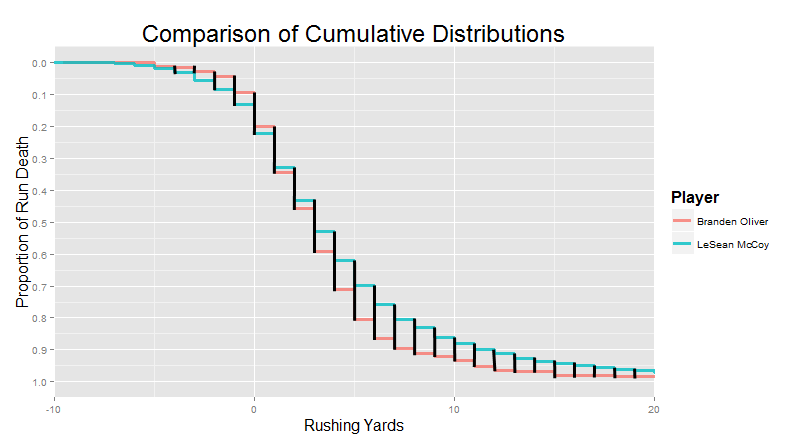

When we run the matching algorithm on McCoy, AP is the #2 match, Reggie Bush in the #3, and Justin Forsett is #7!

“Boom.”

“Boom.”

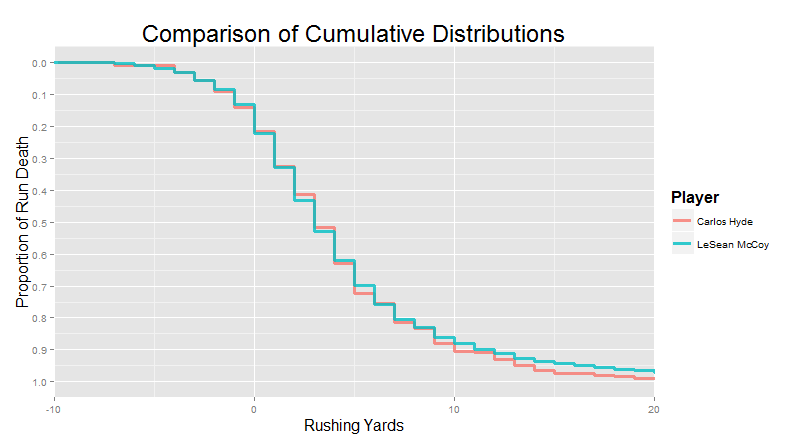

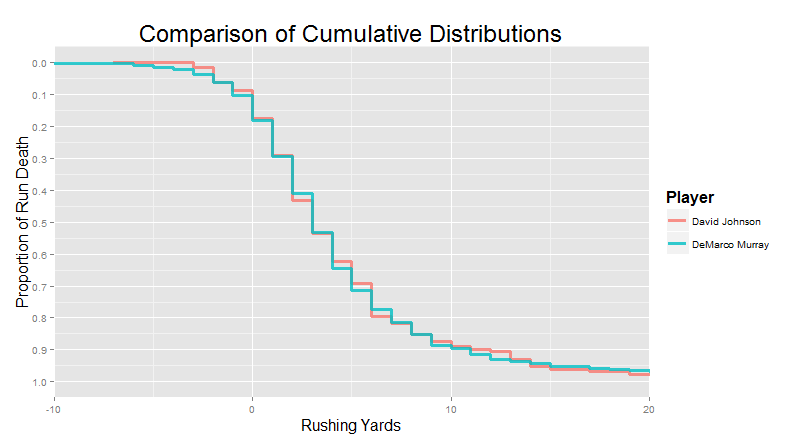

So far so good. Other McCoy matches were pretty interesting. CJ Spiller was #4 and Jonathan Stewart was #6, who I could buy as home-run hitters. But Carlos Hyde was #5, and Lamar Miller was #8, both of whom I usually see as more of a grinder type. Let’s take a look:

I can see why the algorithm likes this as a match! The two distributions are pretty closely aligned for much of the distribution. Like McCoy, Hyde is more likely than average to go down early. And they are about equal as mid-yardage runners, through the contested zone. But the place where Hyde and McCoy are the actually the most different is in hitting home runs. The algorithm doesn’t know that hitting home runs is in part how we were defining McCoy’s output as a runner. To my eye, it looks like the two are different archetypes. McCoy is a classic home run hitter. But Hyde is Grinder who has had his entire distribution shifted to the left due to a bad offensive line – the distribution is shifted, not “spread”. It’s an exceedingly dumb algorithm, so it doesn’t know this on it’s own.

“Actually it’s technically a lazy algorithm. Like, for real.”

“Actually it’s technically a lazy algorithm. Like, for real.”

Remember that literally the only information the algorithm has is the run distribution – it doesn’t have information about sample size, height and weight of the player, usage, years in the league, team, 40 times, nothing. We are exclusively interested in finding similar run distributions (i.e. comparable output) at the moment. But further, the algorithm doesn’t bother trying to figure out which parts of data we give it are the most informative or predictive. It just finds the closest two curves.

That means we need to exercise a little bit of care to interpret these results the right way. They aren’t trying to make predictions or generalizations, they’re simply a measure of similar output. And further, we need to actually look at the matches ourselves and see how the two curves differ, just to make sure it isn’t finding McCoy-Hyde type “false matches”. I’m going to strongly prefer a match where the players overlap for most of the distribution, with just a few places where just one or the other appears slightly better (like the McCoy-AP match). I’m going to be less inclined to “believe” a match where one player is systematically worse than the other in some critical aspect of the distribution – these sort of matches are “biased,” in the sense that the differences between the players are more likely to be due to real differences in production rather than random variance.

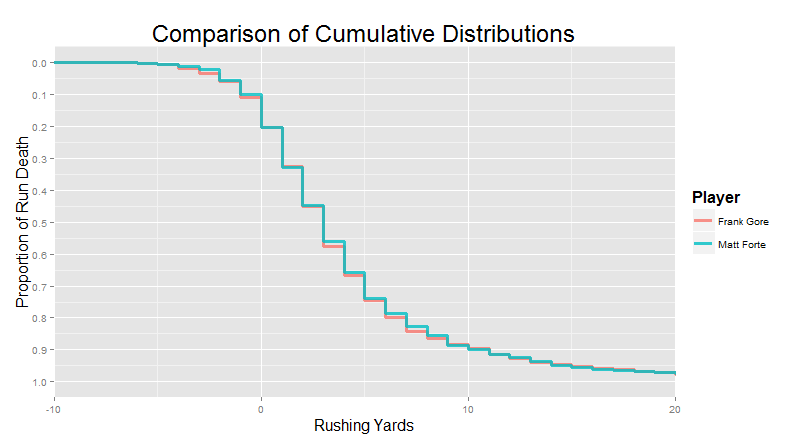

With that in mind, let’s check out the Grinders. Last week, we listed Frank Gore alongside other guys that could match the average at a high volume. That included Morris, MJD, Blount, Ingram, and Lacy.

When we run Frank Gore in the algorithm, Morris is #3, Ingram is #5, and Lacy is #7. And remember, that’s with the algorithm not actually knowing the usage or volume.

One neat thing that stood out to me from the Gore comparables was the #1 match: Matt Forte.

Now, we made a category for “elite pass-catching backs” back in chapter 2, and Forte is certainly that. But what made those other players notable, like Woodhead and Vereen, was the way they leveraged relatively low running volume into a very high effective output. Forte is different. He runs like an every-down back, and carries a huge volume of the running game in addition to being an elite pass-catching back.

“In other words, Forte might catch like Woodhead or Vereen. But he runs like Frank Gore. Their ground production patterns are almost completely identical. However, Forte’s closest match is actually even more appropriate: Arian Foster, a strikingly similar dual-purpose running back. Foster and Forte are pretty close in height, weight, and age, and play similar roles in the passing game (with pretty much the same catch rate and yards per catch).”

“In other words, Forte might catch like Woodhead or Vereen. But he runs like Frank Gore. Their ground production patterns are almost completely identical. However, Forte’s closest match is actually even more appropriate: Arian Foster, a strikingly similar dual-purpose running back. Foster and Forte are pretty close in height, weight, and age, and play similar roles in the passing game (with pretty much the same catch rate and yards per catch).”

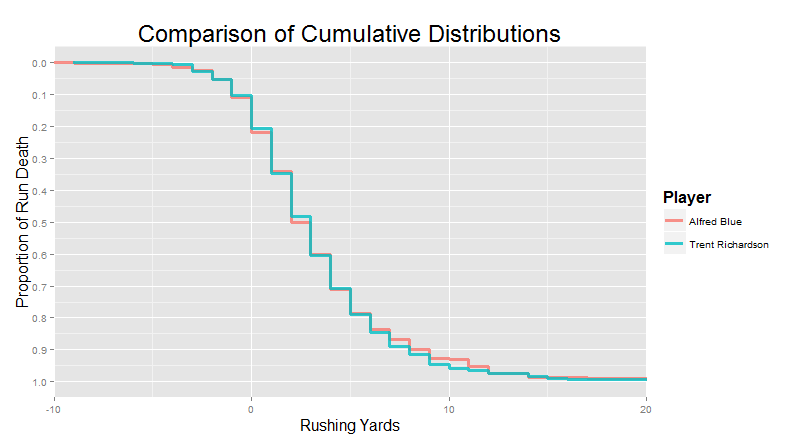

Moving to the JAGs, we see a familiar face at #3 after we run Alfred Blue through the player matcher machine:

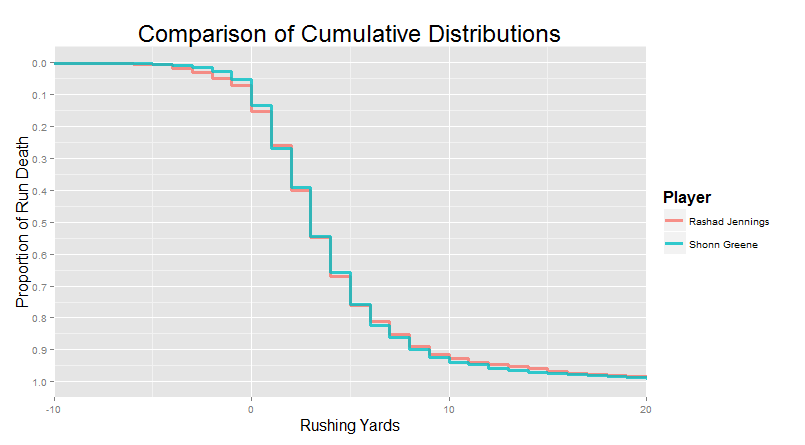

And for the short-yardage Bruisers, Jennings was the #1 match for Greene:

For the pass-catching backs, Pierre Thomas was the #5 match for Woodhead. The top match was Jonathan Grimes, third-down back for the Texans in 2015 during Foster’s absence. Bizarrely, all 5 of Woodhead’s 5 best matches are on the short side, also coming in at 5’9 or 5’10. Coincidence, or a product of the running style? Might be interesting to pursue later.

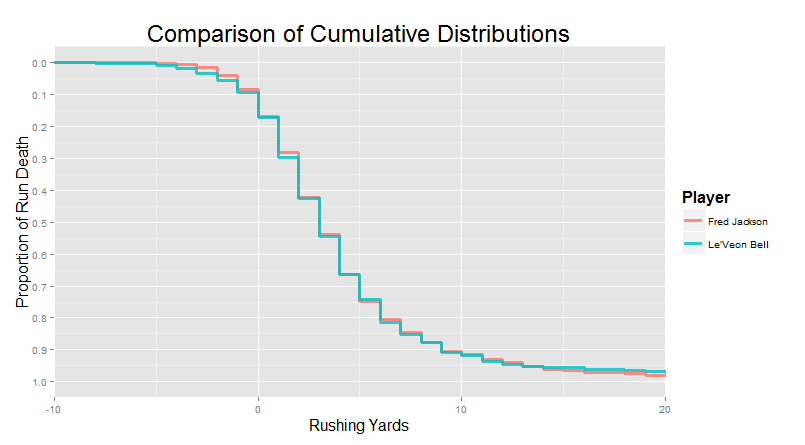

And finally, we can wrap things up with Le’Veon Bell representing the “game-breaking talents.” A few familiar faces pop up - late-career LaDainian Tomlinson is #10 – but the #1 match is a bit of a surprise: Fred Jackson.

“Remember that we’re only looking at seasons this decade, so this doesn’t even include Jackson’s outstanding 2009 season (where he became the first player in NFL history to compile 1,000 rushing and 1,000 kickoff return yards at the same time). I really like this match, though. FJax put in a lot of good years for Buffalo. He was the heart and soul of their ground game for nearly a decade.”

“Remember that we’re only looking at seasons this decade, so this doesn’t even include Jackson’s outstanding 2009 season (where he became the first player in NFL history to compile 1,000 rushing and 1,000 kickoff return yards at the same time). I really like this match, though. FJax put in a lot of good years for Buffalo. He was the heart and soul of their ground game for nearly a decade.”

Yeah, the more I think about the match, the more I like it. Similar builds, and similar pass-catching ability. Le’Veon’s the more explosive player (even compared to FJax’s peak), but old Freddie did once win a camp battle against Marshawn Lynch. He’s no slouch. It also helps that he’s probably made out of diamond dust and epoxy. Dude had his most productive years in his late 20s and early 30s.

“Well, in the NFL at least. But it took him a few years to get to the NFL as a mid-20s undrafted free agent in the first place. During his last season in the United Indoor Football league, he ran for 1,770 yards and 40 touchdowns (plus another 13 passing and returning TDs), then popped on over to Düsseldorf to immediately pick up another 731 yards for Rhein Fire. That’s a hell of a year.”

“Well, in the NFL at least. But it took him a few years to get to the NFL as a mid-20s undrafted free agent in the first place. During his last season in the United Indoor Football league, he ran for 1,770 yards and 40 touchdowns (plus another 13 passing and returning TDs), then popped on over to Düsseldorf to immediately pick up another 731 yards for Rhein Fire. That’s a hell of a year.”

In that vein, another way of looking at this is through Fred Jackson’s highest matches. As the more established player, he’s the known quantity here. Even though we haven’t looked into any predictive modeling yet, seeing which younger players are producing output most similar to established players could potentially be an indication of their talent, role, usage, and/or running style.

Backwards Matching: Moving from Old to Young

So who runs like Fred Jackson? His top three matches come out to be Le’Veon Bell, Giovani Bernard, and late-career LaDainian Tomlinson (when he was with NYJ). We’re looking exclusively at run distributions, but I think it’s interesting that we again get three guys that are also effective pass-catchers, but aren’t typically used similarly to guys like Woodhead and Vereen. One thing that keeps popping up here is the extent to which your ability to gain yards through the air influences the yardage you can get on the ground.

I wanted to see if high-volume running backs with a smaller share of the passing game would similarly elicit mostly other ground-and-pound running backs, so I checked out Marshawn Lynch. And the guys I got back largely fit the bill: the top 10 included Morris, Blount, Ridley, DeMarco Murray, Ryan Mathews, and Chris Ivory. No really young guys that we can point to as producing a “Lynch-like” output yet, but Ivory in particular would have for sure been some of my guesses about who I would most expect to pop up as similar runners, and the distribution-matching algorithm bears this out.

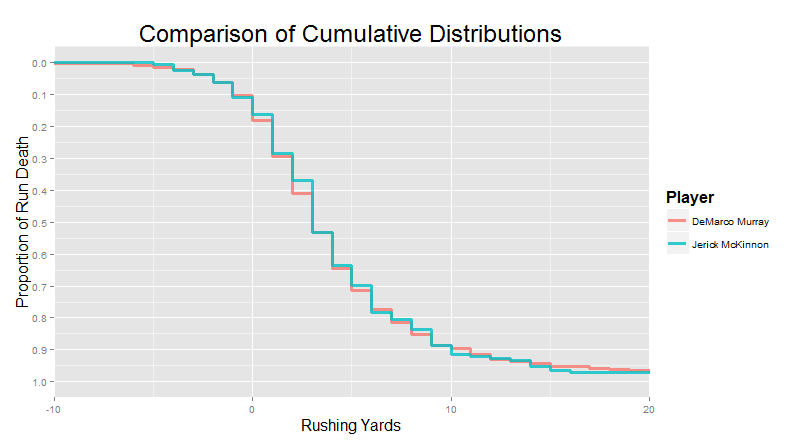

DeMarco Murry, Lynch’s #4, seemed like an interesting follow-up here. He’s known for a really bruising tough-to-tackle running style, but also has historically picked up a fair amount of the passing game as well (just not as much as guys like Forte and Foster). Intuitively, I would definitely expect similar grinders in his matches. But I wondered whether we might also see some Gio-like pass-catching guys.

But that’s not really what we get, for the most part. Murray’s top 5 matches are Marshawn Lynch, Stevan Ridley, LeGarrette Blount, Lamar Miller, and Jonathan Stewart.

I was, however, excited to see two younger matches for Murray:

McKinnon was #9 and David Johnson was #10. Many folks are probably well-aware of McKinnon’s “SPARQ monster” status. An option quarterback out of Georgia Southern, McKinnon entered the combine as a running back in 2014, and finished top-3 among RBs in every single drill. That included a 4.41 40-yard time and, despite being only 5’9, he posted a 40” vertical and an 11-foot broad jump. I really want to draw a parallel to Murray, who had exactly the same 40 time and also stood out on the jumps in his rookie combine, but honestly that’s probably more coincidence than anything else. Still, McKinnon is a darling of the analytics community, and it’s worth taking note that he actually has shown some serious chops on the field too.

“Running the ball, anyways. He was a mess in pass protection his rookie year, which is bad news for a team with a young quarterback to develop. He’s going to need to continue improving there if he even wants to become the reliable backup to AP, though maybe he could back up Teddy and revive the Wildcat.”

“Running the ball, anyways. He was a mess in pass protection his rookie year, which is bad news for a team with a young quarterback to develop. He’s going to need to continue improving there if he even wants to become the reliable backup to AP, though maybe he could back up Teddy and revive the Wildcat.”

Yeah, the whole “freakish athlete” thing aside, I sincerely doubt that McKinnon is the second coming of AP. The algorithm really bears this out: McKinnon’s production doesn’t look like AP. McKinnon’s production looks like that of a bigger, stronger running back than he actually is. If he succeeds in the NFL, he’s going to do it in his own way, and it’s probably going to involve making up for lack of vision by running extremely fast around the people that want to tackle him. McKinnon isn’t even in AP’s top 50 (for the curious, Adrian Peterson’s closest matches are CJ Spiller and Reggie Bush, but I’m not sure this is the appropriate analysis to capture what makes AP special).

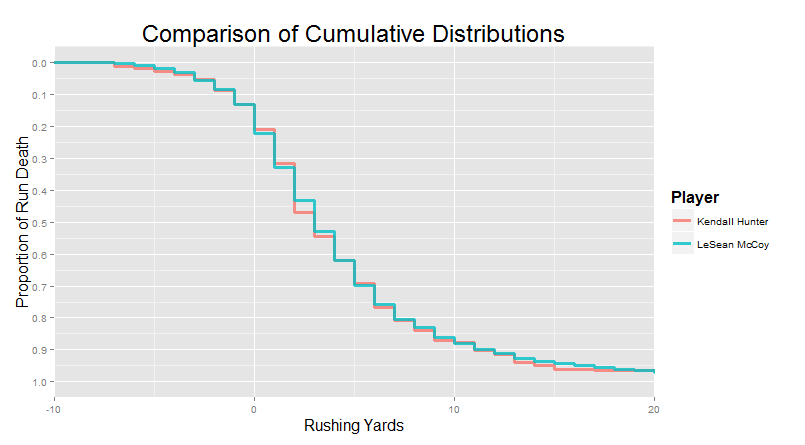

One final backwards match that I want to return to before we move on is LeSean McCoy. McCoy was one of the first guys we talked about when we started exploring this player-matcher system. His matches were a who’s-who of explosive running backs: AP, Reggie Bush, CJ Spiller, Jonathan Stewart, Lamar Miller, etc. But I left out his clear #1 match, because it’s a bit of a weird one. Behold, the #1 match for LeSean McCoy in the entire database:

Kendall Hunter is a bit of a sad case. A visionary talent born in a too-small body with a penchant for horrendous injuries. People forget how good Kendall Hunter looked at times. They loved him in Oklahoma, and a good number of scouts were pretty excited about him coming into the draft. They were just concerned about his size: “If he were two inches taller, we would be talking about him as a top running back”. He ended up falling to SF, where for a while, he looked like one of the best backups in the league. Unfortunately, a torn Achilles and then a torn ACL in back-to-back seasons sapped a lot out of him. He’d be lucky at this point to still be rostered a year or two from now. But for a while, he was running like the real deal.

“Hey, never say never. Guess who swung by Foxborough for a visit a few months ago? It’s good to kick the tires on guys who have flashed like that. Who knows – you might just find yourself another Dion Lewis!”

“Hey, never say never. Guess who swung by Foxborough for a visit a few months ago? It’s good to kick the tires on guys who have flashed like that. Who knows – you might just find yourself another Dion Lewis!”

Forward Matching: Young to Old

The other primary thing we can do with this sort of matching algorithm is to find who the younger players most resemble. Again, this is not the same as predicting who the best players will be. If I wanted to find talent, I would probably start and end with the tape.

But as we’ve shown above, I think this sort of production-matching could potentially uncover some gems. Dion Lewis is a great example: his closest match with an established player is Jamaal Charles. No wonder he looked good this year!

This is sort of the main event of the chapter, so we’re just going to step out of the way and give you the top matches for a bunch of the first and second year players, along with a few of my notes. Here we go!

2015 Rookies

Thomas Rawls (highlights)

Matched Jamaal Charles, but actually looked better. Phenomenal through the contested yards, but also broke out 15-yard runs at double the league-average rate. Super physical, loves run over people. Aggressive North-South style - took the vast majority of his carries between the tackles and doesn’t shy away from contact. Not much involvement in the passing game, and red zone efficiency was not particularly impressive, meaning that fantasy production could be highly variable, but he had one of the best string of games in the league last year. Was never really “off”. Joy to watch. Will almost certainly regress (he’s currently running like a hall-of-fame talent, which is probably unsustainable), but looks to me like one of the best in the class.

Karlos Williams (highlights)

Jamaal Charles, Thomas Rawls, DeMarco Murray. Above-average at all phases of the run. Seems to relish busting through traffic.

David Johnson (highlights)

Lamar Miller, DeMarco Murray, Stevan Ridley. Impeccable balance, oozes power. Has the body control to be a solid pass-catcher too (his route running looks good). Really shined in both middle-distance runs of 3-5 yards and long runs of 10-15 yards. Could be very good, but it’s worth noting that the Cardinals are just packed with talent in the backfield. CJ2K and Ellington are both above-average talents, while Kerwynn Williams has consistently turned up in my analyses as a potential hidden gem.

T.J. Yeldon

Frank Gore, Ronnie Hillman, CJ2K, James Starks. Carried an extremely high load for a rookie (second in active run share behind only Gurley last year) without losing a single fumble. A reliable high-volume Gore/Starks type is pretty much exactly what JAX fans are hoping for here as the best case scenario. Had some trouble getting to the line of scrimmage thanks to a shaky offensive line, but made up ground on his own and kept pace with the league average through the rest of his run distribution. Thanks to both good size and good speed, he was equally effective through the middle and around the end, with a good balance in run direction. Very excited to see this young offense develop together.

Todd Gurley (highlights)

Leon Washington, James Starks, Joseph Randle. He clearly flashed some serious talent on the field, but the modest efficiency is the somewhat predictable consequence of the terrible quarterback situation and questionable offensive line. This is why you build from the inside-out, people. Still, despite carrying the dead weight of a shitty situation, Gurley has the highest rate of 20-yard runs by any starter in the database. Give an inch, and he’ll take a mile. Turned a very high volume into impressive weekly production, though with an unusually high degree of game-by-game variance (as measured by standard deviation in marginal per-game surprisal). Very little involvement with the passing game (and Benny Cunningham is distinctly underrated here for the Rams), but a guy that can carry a big workload as a constant home-run threat is always going to be useful. Our more expansive cluster analysis of players groups him alongside the likes of AP and McCoy.

Tevin Coleman

Knowshon Moreno, Marshawn Lynch, Ryan Mathews. Poor Coleman was an easy target for Falcons fans this year, with his injury issues, fumble-itis, lack of patience, and box stats that were easily overshadowed by Devonta Freeman’s breakout year. Oh, and he got concussed by his bathtub. But quite honestly… I think there’s a not insignificant chance that Coleman is the better runner. Especially blasting through the contested yards, which was a serious deficiency of Freeman’s game this season. I think the Chargers-era Ryan Mathews in particular is a good comparison: a frustrating but talented runner. Hopefully he stays healthier than Mathews.

Ameer Abdullah

Marshawn Lynch, DeMarco Murray, just with fewer long runs. Got hit behind the line a lot, but fought for every goddamned inch, and posted significantly above-average numbers in the 0-10 yards range despite the high stuff rate (though was not much of a home run threat his rookie year). Unfortunate tendency to get tackled just before the first-down marker. I think his comparables speak to his talent, but I think stylistically he’s a really different player, as evidenced by the relatively low proportion of runs up the middle (compared to runs around the end or behind at Tackle). I think he has a reasonable chance of further growing as a home-run threat as well: he led the league in return yards and broke the franchise record for return average, as well finishing 5th in the league in all-purpose yards (among all positions). He also had a great run-pass balance and relatively low game-by-game variance. He’s just good with the ball in his hands, regardless of how you get it to him. If you’re disappointed, you’ve not been paying attention.

Jeremy Langford

Peyton Hillis, Rashad Jennings. Despite being identified by nearly everybody as a pass-catching Matt Forte type of versatile player, on the ground he appears to specialize in short-yardage gains (and was considerably above average in grinding out 0-4 yard runs), but was significantly below-average in the 5-10 yard gains we tend to see from those versatile pass-catching guys (though I won’t deny he can catch a ball, he doesn’t seem to be leveraging that into his running production much). Along that same line, despite his involvement with the passing game, he was run through the middle a lot (compared to the other low-volume pass-catching guys, who tend to run around the end a lot). Was terrible at breaking out long runs, and never really put together a complete game on the ground. My guess here is that the Bears may have been misusing him, trying to slot him in directly into the Forte/Foster role, and found that he wasn’t particularly effective at it. It’s possible that he would look more effective in a more limited role, similar to a Bilal Powell. His ceiling is probably Ray Rice. But at this point, he could just as easily be another Marcel Reece.

Matt Jones

Tre Mason, Bobby Rainey. Looked more electric on the field than his actual production seems to indicate. I’m not seeing a lot to like here on paper (even though I like his tape). Jones just hasn’t shown enough, and is a risk of being a bust unless he makes big strides next year.

Melvin Gordon

Shaun Draughn and Chris Polk, but worse. Sounds about right. Sorry Chargers. Read more about Gordon in the recent quick hit

Javorius “Buck” Allen

Joique Bell, “Damnit” Donald Brown, Cadillac Williams. Overhyped, and failed to exploit a good offensive line. But might still carve out a space for himself as a pass-catching guy. Doesn’t feel like the Ravens back of the future as Forsett starts to wear down.

Duke Johnson

Jacquizz Rodgers, Cedric Benson. Not an auspicious start as a runner. Good pass-catcher though – would be smart to focus on that. Has the potential to be a Vereen/Woodhead type.

David Cobb

Alfred Blue and Trent Richardson, but WAY worse. Nice going Titans, you’ve done it again.

Note: Jay Ajayi only had 49 attempts this year, barely missing the 50-carry cutoff we used. But his limited sample was not particularly impressive. Hopefully he can turn it around.

2015 Sophomores

Carlos Hyde

Jonathan Stewart, Lamar Miller. More tackles for loss than either, but fights through contested yards like a champ. Solid run-first grinder. Success during his rookie contract probably depends a lot on the moves the Niners make this offseason. The whole offense needs to get better or he’s just going to keep running into brick walls.

Jerick McKinnon

DeMarco Murray, a better Stevan Ridley. Explosive runner, outstanding physical tools, could be the running back of the future for the Vikings. The rest of his game is still in doubt (though a bit beyond the scope of this investigation).

Jeremy Hill

Maurice Jones-Drew and Willis McGahee. Regressed considerably this year, though. Further investigation showed that the big change was in the first 2 yards from the line of scrimmage: he’s having trouble making it through the initial hole (but when he does, he looks about the same). Should mention that his rookie year was a bit of an outlier – he was one of the best-looking short yardage runners in the league in 2014. Fast for his size, but doesn’t get to show it much with all the runs up the middle (where his bruising size is the more important asset). Seems capable of carrying a heavy load if anything happens to Gio, but his involvement in the passing game has thus far been very limited.

Charcandrick West

Jacquizz Rodgers, Steven Jackson, Doug Martin, Tim Hightower. Right on the border of looking like a tier-2 grinder. Clearly capable of carrying a high load, but is limited as a threat through the air, and had trouble break through for double-digit yardages.

Bishop Sankey

Shonn Greene. Rashad Jennings but worse at 10+ yards. Looks like a decent short-yardage guy. Could still come good as a volume guy, but the balance still seems to be tilting very much the wrong way. Probably not an every-down back.

Devonta Freeman

Brandon Bolden. CJ Spiller but WAY worse for the first five yards. Currently looks like a home-run hitter boom/bust type, but I have a hunch that the “boom” in this case is the sound of Patrick DiMarco leveling linebackers rather than anything special that Freeman is doing in the open field (though to his credit, he is very fast – it’s a good pairing, and smart offensive design).

Latavius Murray

Darren McFadden (to an uncanny extent), Steven Jackson, 2010 Brandon Jackson. I think Oakland fans would be pretty happy with a more resilient and more consistent early-career McFadden.

Alfred Blue

poopoo. Improvement over his god-awful rookie year, though.

Terrance West

Willis McGahee, Lorenzo Taliaferro. Bilal Powell but worse. Probably good enough to continue playing in the NFL, but coaches seem to hate his demeanor and immaturity.

Antonio Andrews

Jackie Battle. Looked better at the end of this past year, though.

Isaiah Crowell

Not really anybody that is particularly similar. Javon Ringer or Ryan Torain maybe? Tre Mason, kind of. Regressed in 2015. Probably not good enough to be a feature back.

Tre Mason

Also not really anybody. Dujuan Harris? The algorithm places him as far from Jamaal Charles as possible (match 178 out of 180). Was just awful running the ball this year.

Charles Sims

Dexter McCluster kind of?

Andre Williams

Literally the worst run distribution I have ever seen. Absolutely terrible. Should not be playing professional football. I was legitimately worried that I had made some sort of error in the data processing.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

- We can find the “closest” run distributions for different players using an algorithm to find the shortest distance between the curves. We used a few tricks and settled on “Nearest Neighbor Retrieval”.

- Finding matches from the archetypes we explored last time allowed us to find other players who seem to belong to that archetype. CJ Spiller appeared to be a home run hitter, Jonathan Grimes a pass-catching back, and Fred Jackson looked suspiciously like a game-breaking talent.

- The algorithm helped identify Matt Forte and Arian Foster (who are extremely closely matched) as an interesting case of elite pass-catchers who still run like Grinders (carrying a high volume when active and producing an output similar to Frank Gore).

- “Backward matching” entailed the process of using older veterans to find younger players who are running in a similar way. Le’Veon Bell, Giovani Bernard looked a lot like FJax. Jerick McKinnon and David Johnson looked a lot like DeMarco Murray. Kendall Hunter looked like he maybe could have been a McCoy type runner.

- “Forward matching” entailed the process of running the younger players through the algorithm to see which established players they most resemble. All of the rookie and sophomore running backs are described above, along with some notes.