Unpacking Run Distributions

Last time, we talked about a few summary statistics that describe a “typical run”, including a number of measures of central tendency like the mean, median, and mode. We also proposed some “Rules of Run Quantiles” - the “1-3-5 rule” and the “10 at 10 rule”.

“And most importantly, we introduced the only thing that really mattered: the idea of a run as a sample from a probability distribution. We can see an estimation of that source distribution using density plots and cumulative density plots.”

“And most importantly, we introduced the only thing that really mattered: the idea of a run as a sample from a probability distribution. We can see an estimation of that source distribution using density plots and cumulative density plots.”

The idea of run distributions really is valuable, so we’re going to explore them for a while. Here, we’re going to illustrate what can be learned when a particular player is plotted against the average of all runs.

“Even for a stat-head, comprehensively visualizing your data should always be step one, before diving in with the fancy statistical tests. Your brain is very good at understanding pictures. And personally, regardless of how many fancy numbers you can produce, I don’t trust something that I can’t see. It’s not good enough to tell me that a guy’s yards per carry is such and such. If you want me to believe that a guy has been under-performing or is a secret talent, show me (in both the data and the tape).”

“Even for a stat-head, comprehensively visualizing your data should always be step one, before diving in with the fancy statistical tests. Your brain is very good at understanding pictures. And personally, regardless of how many fancy numbers you can produce, I don’t trust something that I can’t see. It’s not good enough to tell me that a guy’s yards per carry is such and such. If you want me to believe that a guy has been under-performing or is a secret talent, show me (in both the data and the tape).”

Well said. It can be helpful to kick things off looking at the true greats, so that the differences that set “good runners” apart are really easy to spot. To that end, we’re going to start today by taking a look at the generational talent who might just be the best running back in football over the past few years.

"Jamaal Charles!"

"Jamaal Charles!"

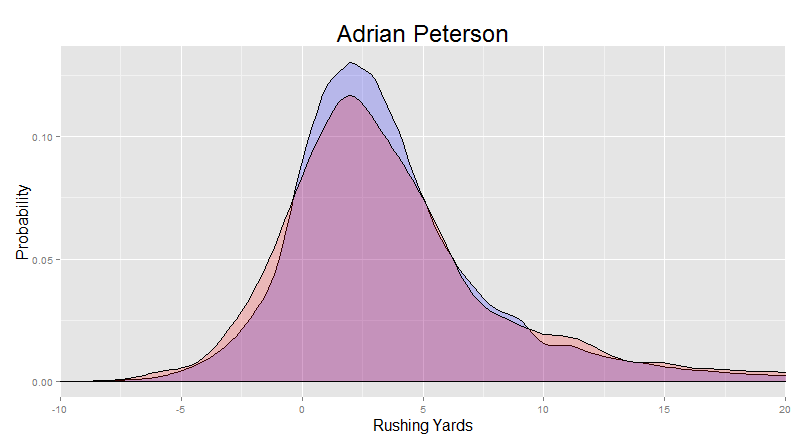

… OK, widely considered to be the best running back in football over the past few years. I’m speaking, of course, of Adrian Peterson. For this and every other plot below that involves the league-average, the league as a whole is BLUE while the named player is RED.

As you can see here in the density plot, AP, on average, is actually more likely to get hit behind the line of scrimmage than the rest of the league.

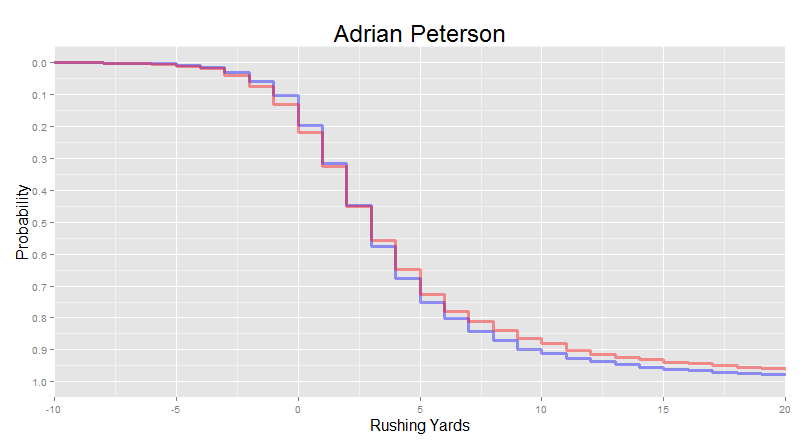

“And this is echoed in the cumulative density plot, where he shows a greater proportion of runs stopped by -2, -1, and 0 yards than the league-average.”

“And this is echoed in the cumulative density plot, where he shows a greater proportion of runs stopped by -2, -1, and 0 yards than the league-average.”

There is a lot of potential reasons for this. Relatively poor blocking by the offensive line can result in getting hit a lot behind the line of scrimmage, so much so that Football Outsiders actually attributes 120% of tackles for loss to the O-line instead of the running back (i.e. “it’s their fault and then some”). We think there are also some (mostly run-style related) attributes of the running backs that can cause a higher number of early hits as well. For instance, players that spend longer behind the line trying to find the best hole might have a bit of a boom-bust output, because they’re intentionally forgoing a yard or two early in the run (i.e. they don’t immediately get as far downfield as possible) for the chance at a big gain later in the run. This is often referred to positively as “patience” and negatively as “dancing”, depending on the particular point that the announcer or analyst is trying to make. This sort of shifty running can be very successful if the running back is sufficiently quick and elusive. We’ll return to this idea later.

“I feel like I also have to mention that there are also potential schematic reasons for a higher probability of early hits, regardless of the quality of the particular runners and blockers involved. For example, predictable offenses, obvious running formations, run-first situations, and bad quarterbacks allow defenses to key more heavily on the run. Asking a running back to operate under such conditions is tough, and can lead to tackles for loss above the typical rate. AP isn't very involved in the passing game, and the Vikings haven't had a decently threatening passing attack since maybe 2009. Defenses can key on the run against AP.”

“I feel like I also have to mention that there are also potential schematic reasons for a higher probability of early hits, regardless of the quality of the particular runners and blockers involved. For example, predictable offenses, obvious running formations, run-first situations, and bad quarterbacks allow defenses to key more heavily on the run. Asking a running back to operate under such conditions is tough, and can lead to tackles for loss above the typical rate. AP isn't very involved in the passing game, and the Vikings haven't had a decently threatening passing attack since maybe 2009. Defenses can key on the run against AP.”

But regardless of why AP tends to run for negative yards more often than usual, the next phase of the run – the contested yards – really shows his talent. In the density plot, we can see that he is less likely than average to be stopped within the first five yards.

“In the cumulative density plot, we can see him start to make up ground for those early hits, starting from the line of scrimmage. By the time we get to 5 yards, AP is about 5% less likely to have been stopped than the average, despite having been tackled much more often behind the line of scrimmage. If he can make it to the line of scrimmage, he’s doing a significantly better job than average battling through the contested yards.”

“In the cumulative density plot, we can see him start to make up ground for those early hits, starting from the line of scrimmage. By the time we get to 5 yards, AP is about 5% less likely to have been stopped than the average, despite having been tackled much more often behind the line of scrimmage. If he can make it to the line of scrimmage, he’s doing a significantly better job than average battling through the contested yards.”

And all of that momentum is carried in to the open field phase. In the density plot, it’s spread pretty thin throughout that long right tail, but you can still clearly see a pretty significant bump in the runs that go for 10-15 yards.

“These ‘home runs’ are much more clear in the cumulative density plot. His run survival is above average by 3 yards, and stays above average for all yardages above that. Give AP a reasonable amount of room at the start of a run, and he is going to get you more yards than anyone else.

“These ‘home runs’ are much more clear in the cumulative density plot. His run survival is above average by 3 yards, and stays above average for all yardages above that. Give AP a reasonable amount of room at the start of a run, and he is going to get you more yards than anyone else.

It’s worth noting here how subtle these differences look at first glance. One thing to keep in mind again is: very good running backs tend to get more carries, so the “average” density here tends to reflect a very high talent level.

“In fact, about 20% of all RB runs in the NFL over the past six years are attributable to just ten players: Gore, McCoy, Lynch, CJ2K, Peterson, Forte, Foster, Steven Jackson, Murray, and Morris. Combined, they’ve made 13,770 regular-season rushing attempts since 2010.”

“In fact, about 20% of all RB runs in the NFL over the past six years are attributable to just ten players: Gore, McCoy, Lynch, CJ2K, Peterson, Forte, Foster, Steven Jackson, Murray, and Morris. Combined, they’ve made 13,770 regular-season rushing attempts since 2010.”

That’s a lot of talent there. Beating the average is tough, and any runner that is consistently superior in any phase of the run is immensely valuable. In a game of inches, a 5% increase in the probability of keeping a run alive to 5 yards is a boon. Even a guy that can keep pace with this league average at a high volume is valuable.

“And those guys are hard to find. Half of all active running backs over this 6-year period accumulated fewer than 60 total attempts. A quarter of all running backs since 2010 never made it past 15 total carries. Teams are constantly cycling through prospects to try to land on a workable backfield.”

“And those guys are hard to find. Half of all active running backs over this 6-year period accumulated fewer than 60 total attempts. A quarter of all running backs since 2010 never made it past 15 total carries. Teams are constantly cycling through prospects to try to land on a workable backfield.”

Those volume guys that can keep pace with the league average with a very high load are what I call “grinders”. In my explorations of run distributions, I’ve identified about six archetypal run distributions, reflecting different types of runners, possibly with different styles or talents.

“To be clear, there is no math in these determinations. That will come later.”

“To be clear, there is no math in these determinations. That will come later.”

… But winging it is fun, and classifying things is super fun. So let’s dive in.

Six Running Back Archetypes

The Grinder

Others: Morris, Maurice Jones-Drew, Ingram, Lacy.

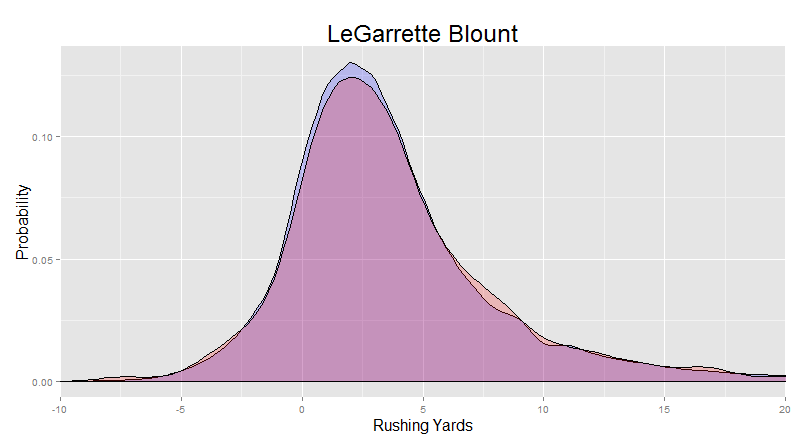

As we mentioned above, being able to keep pace with the rest of the league at a high volume is hard, and a running back capable of doing that can contribute a lot to a team’s ground game. These players churn out yards and break out big runs at a respectable pace, and are able to do so even with a high usage rate. Teams love to lean on these guys, and their constant presence on the field as the workhorse back can offer a lot of stability to an offense.

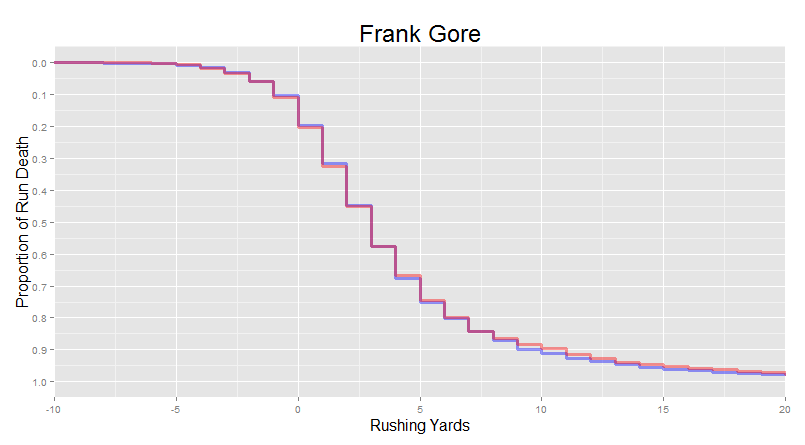

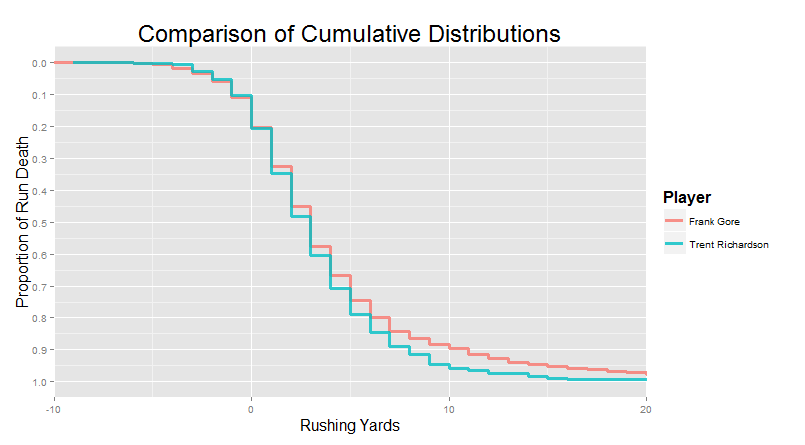

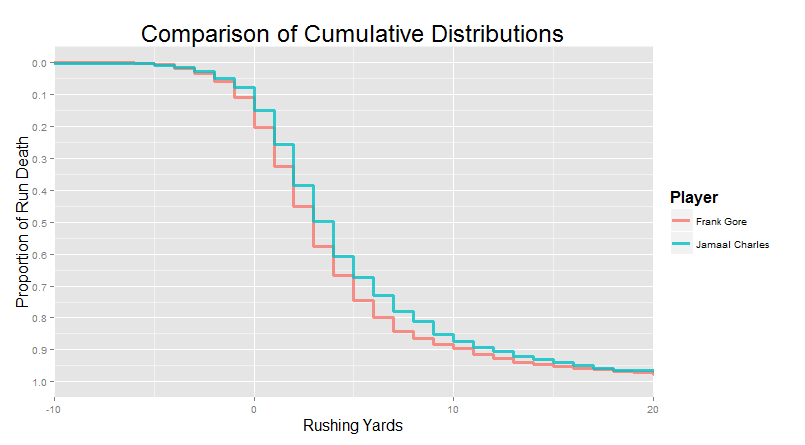

“Frank Gore is a really fantastic example of this type of running back. He has never spent a single season in the past six years with fewer than half of his team’s RB rushing attempts. What’s more, his regular season usage has increased every single year since 2010. He carried 72% of the running back load in 2014 for the 49ers, his 10th year in the league, then nearly 80% of the running back load for the Colts in 2015. Though he’s slowing down a bit now, his running this decade is pretty much spot-on the average.”

“Frank Gore is a really fantastic example of this type of running back. He has never spent a single season in the past six years with fewer than half of his team’s RB rushing attempts. What’s more, his regular season usage has increased every single year since 2010. He carried 72% of the running back load in 2014 for the 49ers, his 10th year in the league, then nearly 80% of the running back load for the Colts in 2015. Though he’s slowing down a bit now, his running this decade is pretty much spot-on the average.”

In short, these grinders are really just characterized by two things: a high usage, and a league-average run distribution.

But what I think is significantly more interesting are the running backs that are defined by how their distributions differ from the league-average. Let’s take a look at some.

The Home Run Hitter

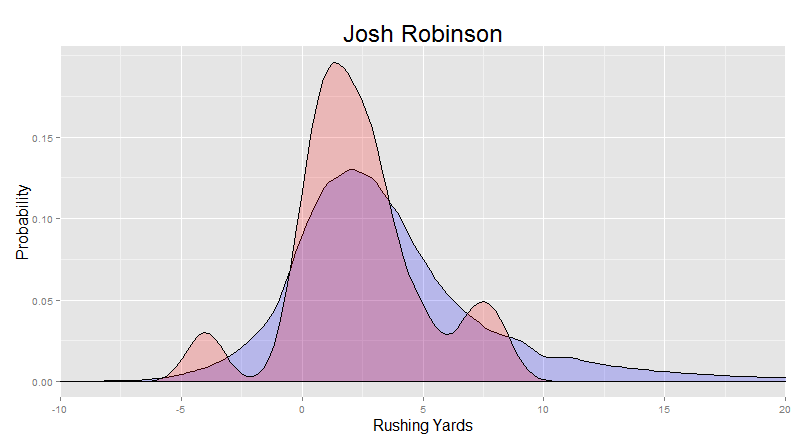

Others: Adrian Peterson, Reggie Bush, Christine Michael

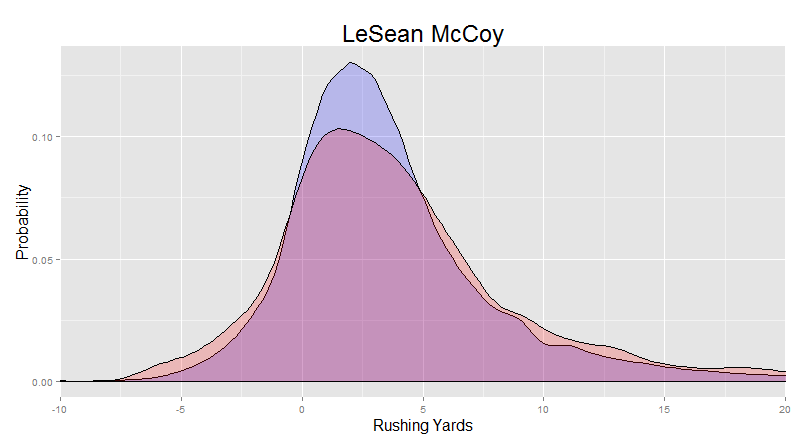

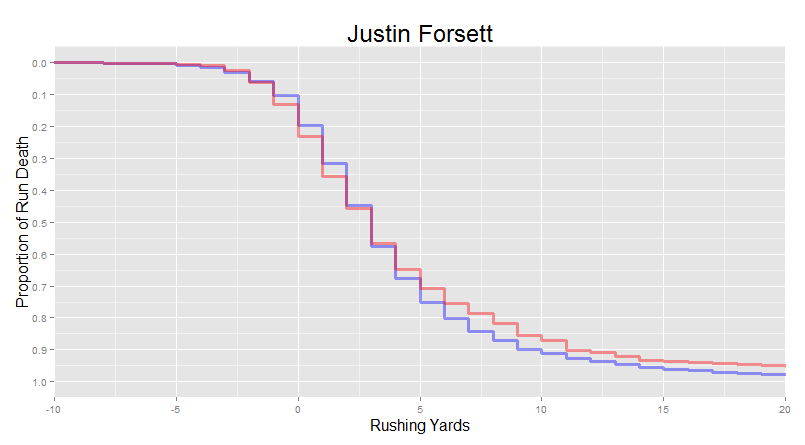

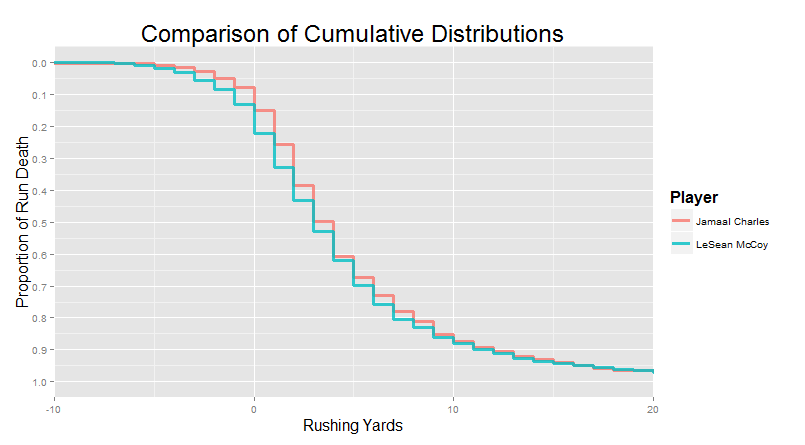

The home run hitter has both a greater than average chance of going down early, and a greater than average chance of breaking a long run. Essentially, the whole density curve is spread out.

“This seeming unpredictability can actually provide a bit more utility than you might expect. Remember that about half of all runs already go 3 yards or less. That’s not enough to reliably get 1st downs. In line with this, other advanced models (like that at numberfire) tend to show that most runs have a negative net expected value. It can be worth it to have some runs go for 0 yards instead of 2 yards if it’s counterbalanced by having other runs go for 8 or 10 yards instead of 3. There’s not much of a difference between 0 and 2 yards in how much they help a drive be successful, but a 10+ yard run generally goes for a 1st down and can dramatically improve the chances of scoring on a drive. These are the Sammy Sosas of football – lots of strikeouts, but also plenty of home runs.”

“This seeming unpredictability can actually provide a bit more utility than you might expect. Remember that about half of all runs already go 3 yards or less. That’s not enough to reliably get 1st downs. In line with this, other advanced models (like that at numberfire) tend to show that most runs have a negative net expected value. It can be worth it to have some runs go for 0 yards instead of 2 yards if it’s counterbalanced by having other runs go for 8 or 10 yards instead of 3. There’s not much of a difference between 0 and 2 yards in how much they help a drive be successful, but a 10+ yard run generally goes for a 1st down and can dramatically improve the chances of scoring on a drive. These are the Sammy Sosas of football – lots of strikeouts, but also plenty of home runs.”

It’s important to note that at “home run” does not necessarily mean taking one to the house. McCoy gains 20 yards or more only 3% of the time, compared to the league average of 2% of the time. But he gains at least 7 yards almost 20% of the time, compared to only 15% for the league average. A team working with a 2nd and 3 will convert for a first down a good amount of the time, so a 1 in 5 chance of breaking out a 7-yard run can be well worth a few early hits. It does mean that these backs are pretty boom-bust, however. It is completely expected for McCoy or Christine Michael etc. to have stretches of almost complete ineffectiveness.

“This is pretty apparent in McCoy’s game log from this past 2015 season. Week 1: 17 carries against IND for 41 yards (2.1 YPC), with a long of 16. Week 2: 15 carries for 89 yards (5.9 YPC) against the Patriots, with a quarter of his runs going for over 10 yards. Week 3: 11 runs for 16 yards against Miami (1.5 YPC), with only a single run over 5 yards. And finally, week 4: 17 carries for 90 yards against CIN, thanks to a long of 33 and a host of runs over 5. Some of this is defensive variance, but a lot of this is also attributable to the inherent streakiness of these types of runners.”

“This is pretty apparent in McCoy’s game log from this past 2015 season. Week 1: 17 carries against IND for 41 yards (2.1 YPC), with a long of 16. Week 2: 15 carries for 89 yards (5.9 YPC) against the Patriots, with a quarter of his runs going for over 10 yards. Week 3: 11 runs for 16 yards against Miami (1.5 YPC), with only a single run over 5 yards. And finally, week 4: 17 carries for 90 yards against CIN, thanks to a long of 33 and a host of runs over 5. Some of this is defensive variance, but a lot of this is also attributable to the inherent streakiness of these types of runners.”

So what’s the opposite of this type of streaky runner, you ask?

The Bruiser (Short-Yardage Specialist)

Others: Daniel Thomas, BenJarvus Green-Ellis, post-Denver Peyton Hillis.

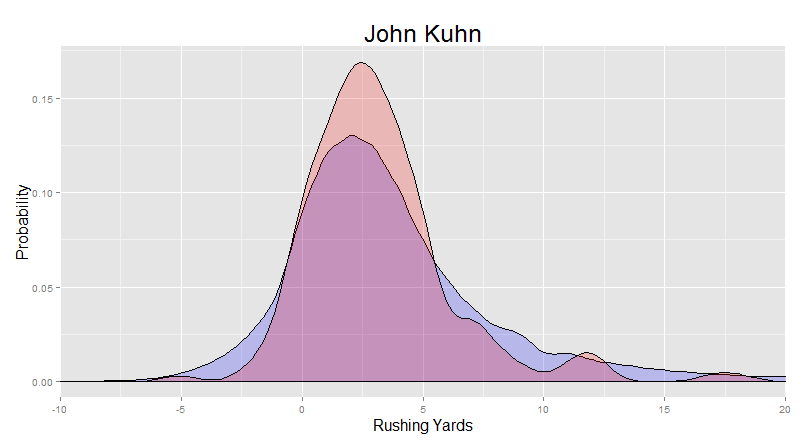

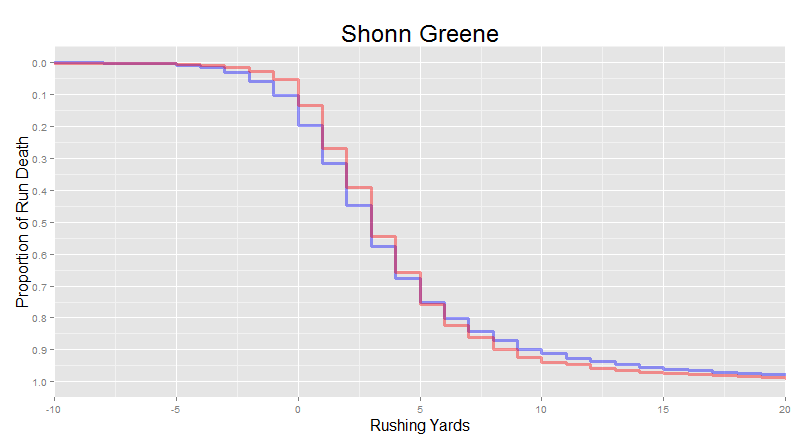

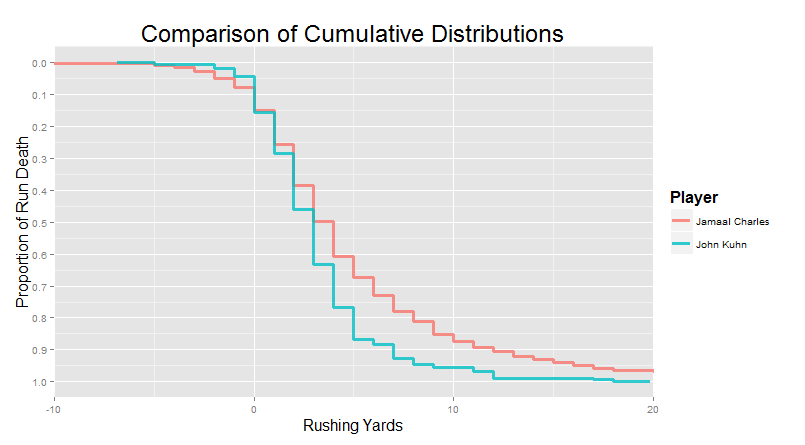

In contrast to the home-run hitter, the Bruisers are terrible at long runs, but they hit the line hard, fall forward, and refuse to go down before picking up a couple of yards.

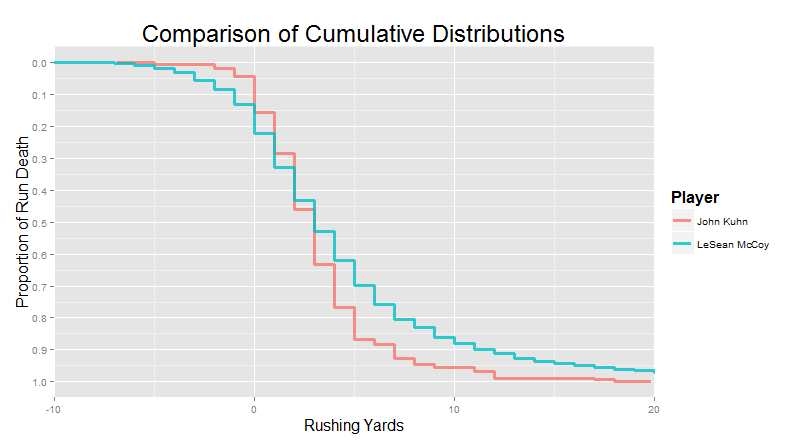

“Having a short-yardage specialist on your team can be a huge asset. Let’s say you need just 1 yard. McCoy gains at least a yard 67% of the time, but Kuhn will get you a yard 72% of the time. And that’s almost definitely a gross underestimation of their different expected values in an actual 3rd and inches situation, because Kuhn is generally only utilized in instances where the defense can heavily key on the run, and his run distribution still shows that he breaks through for positive yardage more often the McCoy does even against those heavy fronts.”

“Having a short-yardage specialist on your team can be a huge asset. Let’s say you need just 1 yard. McCoy gains at least a yard 67% of the time, but Kuhn will get you a yard 72% of the time. And that’s almost definitely a gross underestimation of their different expected values in an actual 3rd and inches situation, because Kuhn is generally only utilized in instances where the defense can heavily key on the run, and his run distribution still shows that he breaks through for positive yardage more often the McCoy does even against those heavy fronts.”

Essentially, these guys are good at trucking dudes. But juking defenders out of their shoes is not generally in their wheelhouse. A twenty-yard McCoy run includes plenty of impossible changes in direction, with cuts so hard it breaks ankles. A twenty-yard Kuhn run “looks like a rugby scrum”.

“The complementary nature of home run hitters and short-yardage bruisers is really apparent when you look at their direct comparison.”

“The complementary nature of home run hitters and short-yardage bruisers is really apparent when you look at their direct comparison.”

These two player archetypes are natural complements. The home run hitters tend to be below-average at short gains and above-average at long gains, while the bruisers can reliably get you a handful yards, but run the open field with all the grace of a newborn calf.

These three types of players that are each useful to teams in different ways. Now we think it’s now a good time to illustrate what bad players look like.

The JAG

Others: Alfred Blue, Bernard Pierce, Joique Bell, Tre Mason, LaRod Stephens-Howling

Sometimes, these guys will (unfortunately) get serious play time. Alfred Blue was the leading rusher for the division-winning Texans this past year (2015). But you basically only want them around as a cheap backup option. If they are the feature back, then something went very wrong.

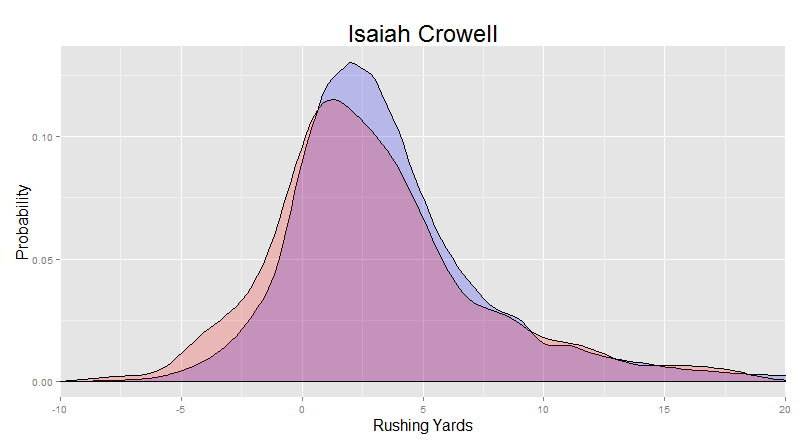

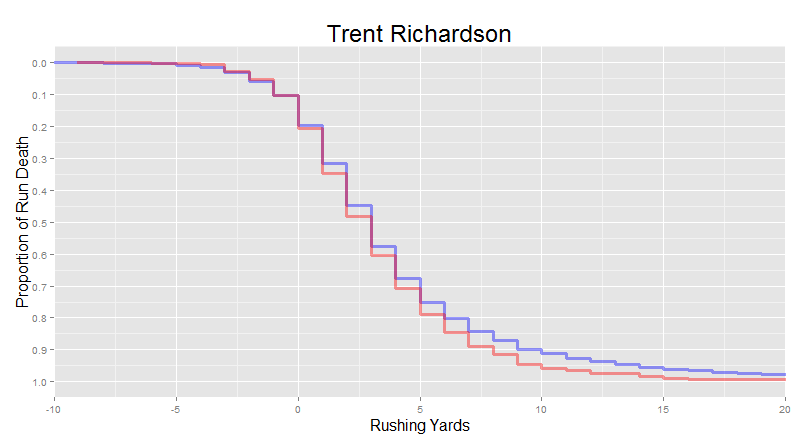

Essentially, this group is defined only by their deficiencies. They are above-average at nothing (in terms of run distributions, anyways), and clearly suffer in at least one phase of the run.

“We’ve actually lumped together players here with different deficiencies. Mason and Crowell get creamed a lot at short yardages, but still have the talent to break out big runs, and they make up a bit of ground during the contested yards (compared to the average). They fight hard, but tend to hurt their teams by getting stopped early at such a high frequency. In contrast, Richardson and Blue tend to get to the line of scrimmage just as well as Frank Gore, but they simply can’t fight through the contested yards anywhere near as well. They hit the pile and fall over. Honestly, there are just a lot of different ways for a dude to be bad, we just didn’t think it was interesting enough to start carving them up into different camps.”

“We’ve actually lumped together players here with different deficiencies. Mason and Crowell get creamed a lot at short yardages, but still have the talent to break out big runs, and they make up a bit of ground during the contested yards (compared to the average). They fight hard, but tend to hurt their teams by getting stopped early at such a high frequency. In contrast, Richardson and Blue tend to get to the line of scrimmage just as well as Frank Gore, but they simply can’t fight through the contested yards anywhere near as well. They hit the pile and fall over. Honestly, there are just a lot of different ways for a dude to be bad, we just didn’t think it was interesting enough to start carving them up into different camps.”

It’s likely that a lot of those quick washouts at the bottom of the roster would also produce distributions like these. But their small samples in actual NFL games leads to some unusual-looking distribution shapes.

Hard to learn much from that. We come back to the effect of small sample sizes in chapter 4.

But the JAG distribution raises an interesting question: if there are players that are consistently below-average in all phases of the run, and if the “average” in this case is heavily influenced by guys like Gore and Peterson, then is it even possible to be above-average in all phases of the run without any apparent weaknesses? Remember, not even AP himself is above average at everything – he actually looks distinctly like a home-run hitter, right down to the high frequency of lost yardage.

“Short answer: Oh yeah.”

“Short answer: Oh yeah.”

Game-Breaking Talents

Others: none that we can point to with much confidence yet. Dion Lewis, David Johnson, and Thomas Rawls look promising.

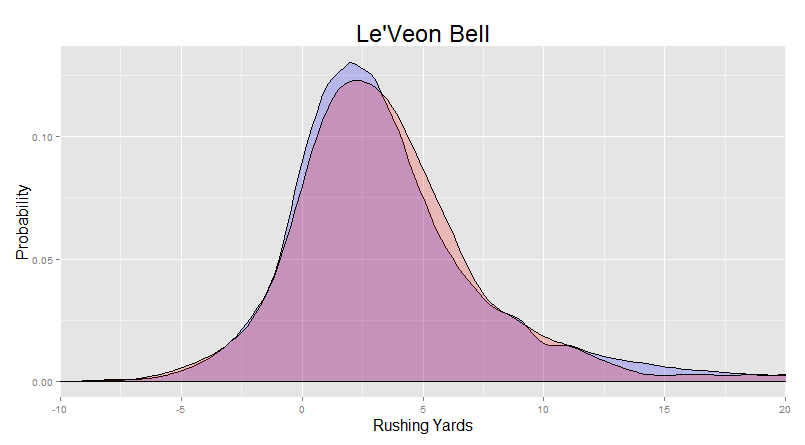

There are just a handful of players in the database that have consistently been above-average in most or all phases of the run. Sometimes, everything just seems to come together for a player. Vision, patience, toughness, athleticism: when it all comes together in a single player, it can be a thing of beauty to watch.

“Le’Veon Bell’s 2014 tape includes, without a doubt, some of the best running of the decade. The game is just moving in slow motion for him. No step is out of place, he cuts on a dime, he can plow through defenders like they aren’t even there, and no crease is too small – he’s just not going to miss an opening. The tape from his three week stretch against TEN, NO, and CIN that year belongs in the MoMA. In three consecutive games, he ran for 484 yards and caught 16 passes for an additional 227 yards. That’s 711 scrimmage yards (along with five touchdowns) in three games. I mean, just look at him.”

“Le’Veon Bell’s 2014 tape includes, without a doubt, some of the best running of the decade. The game is just moving in slow motion for him. No step is out of place, he cuts on a dime, he can plow through defenders like they aren’t even there, and no crease is too small – he’s just not going to miss an opening. The tape from his three week stretch against TEN, NO, and CIN that year belongs in the MoMA. In three consecutive games, he ran for 484 yards and caught 16 passes for an additional 227 yards. That’s 711 scrimmage yards (along with five touchdowns) in three games. I mean, just look at him.”

It’s worth noting again that Le’Veon’s run distributions may not look hugely different from the average. But small differences on the plot are the result of big differences on the field. Think of it this way: about 1 in 6 of the runs where Frank Gore would normally go down between 0-3 yards, Le’Veon takes it 5 yards. He shifts the whole run distribution to the right.

There is one exception to this, however. A player so good, so game-breakingly talented, that the difference between him and everybody else is acutely obvious.

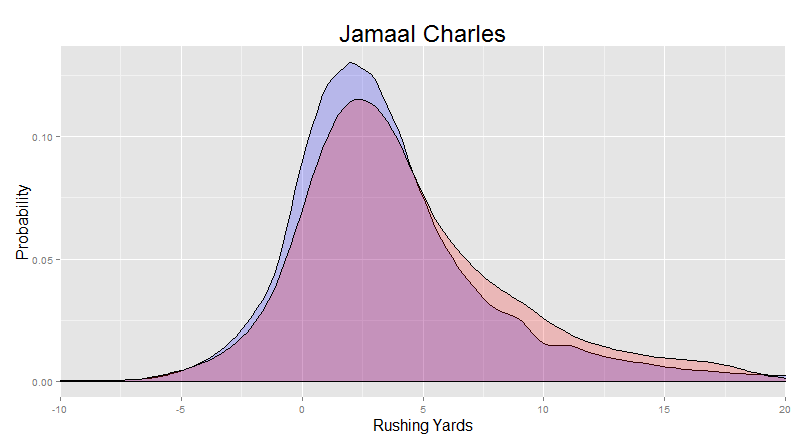

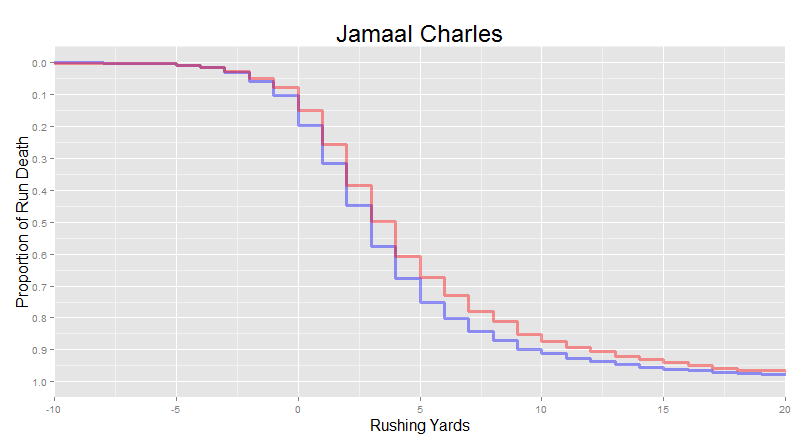

Jamaal Charles is Impossible

“Charles has played eight seasons for the Chiefs, and has NEVER had a single season in his entire career with an average yards per carry less than 5.”

“Charles has played eight seasons for the Chiefs, and has NEVER had a single season in his entire career with an average yards per carry less than 5.”

“Some folks deride his lack of volume stats - The Chiefs like to keep him below 20 carries per game - but he's perfectly capable of carrying immense loads when needed. He’s actually the first player since Jim Brown and O.J. Simpson to break 220 rushing yards in a game three different times. He also has the highest career yards per carry ever. And have I also mentioned that he’s one of the best receiving backs in the game?”

“Some folks deride his lack of volume stats - The Chiefs like to keep him below 20 carries per game - but he's perfectly capable of carrying immense loads when needed. He’s actually the first player since Jim Brown and O.J. Simpson to break 220 rushing yards in a game three different times. He also has the highest career yards per carry ever. And have I also mentioned that he’s one of the best receiving backs in the game?”

“He’s just as much of a home-run threat as McCoy, but the same time, he’s also just as good (if not better) of a short-yardage runner as John Kuhn.”

“He’s just as much of a home-run threat as McCoy, but the same time, he’s also just as good (if not better) of a short-yardage runner as John Kuhn.”

Bernie, you’re gushing a bit.

“Look, I’m just saying, Jamaal Charles went in 3rd round of the 2008 draft. We had the Saints 3rd round pick after they traded up 3 spots in the 1st to take Sedrick Ellis (which was fine by us - we still got Jerod Mayo at the 10 spot). Just a few months removed from fielding probably the greatest offense of all time, we were five spots away from picking up a generational talent at running back in the third round. Can you just imagine what that Pats team would have looked like? Tom Brady, Wes Welker, Randy Moss, and Jamaal Charles in a Bill Belichick offense? With a defense that included Mayo, Wilfork, Junior Seau, Rodney Harrison, Tedy Bruschi, and Mike Vrabel? And a special teams that just picked up Matthew Slater, with Gostkowski at kicker? How do you even begin to approach a team like that?”

“Look, I’m just saying, Jamaal Charles went in 3rd round of the 2008 draft. We had the Saints 3rd round pick after they traded up 3 spots in the 1st to take Sedrick Ellis (which was fine by us - we still got Jerod Mayo at the 10 spot). Just a few months removed from fielding probably the greatest offense of all time, we were five spots away from picking up a generational talent at running back in the third round. Can you just imagine what that Pats team would have looked like? Tom Brady, Wes Welker, Randy Moss, and Jamaal Charles in a Bill Belichick offense? With a defense that included Mayo, Wilfork, Junior Seau, Rodney Harrison, Tedy Bruschi, and Mike Vrabel? And a special teams that just picked up Matthew Slater, with Gostkowski at kicker? How do you even begin to approach a team like that?”

Instead, the Pats took Shawn Crable, Brady tore his ACL on the first game of the season, spygate cost the Pats a 1st round pick, and the team became the first ever in the modern format (since 1990) to miss the playoffs despite having 11 wins.

“… We don’t talk about 2008 much around here.”

“… We don’t talk about 2008 much around here.”

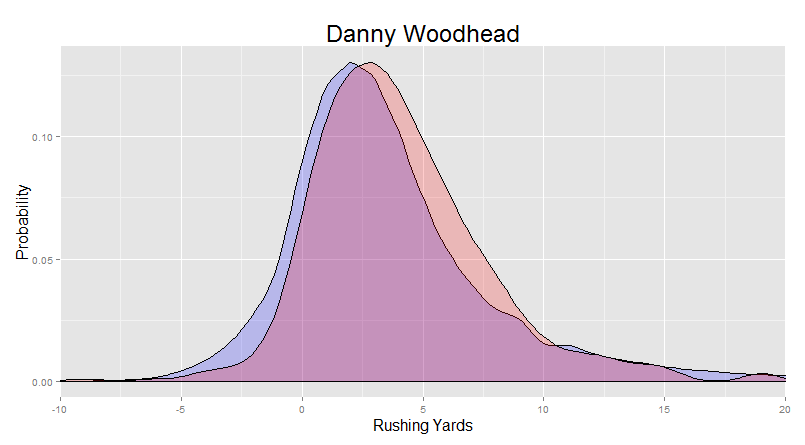

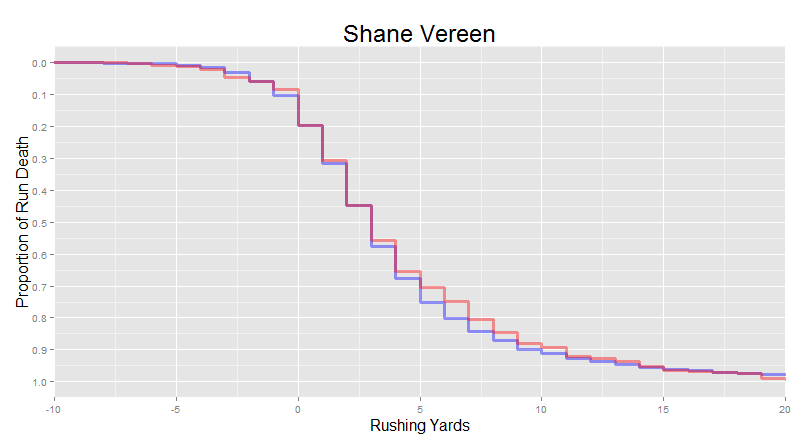

Well, 2008 was a notable year for two running backs that ended up meaning a lot to New England in the coming years. Danny Woodhead entered the league as an undrafted free agent, and Shane Vereen begin his college career at Cal. These two are really great illustrations of the last archetype we’re going to be talking about today.

Elite Pass-Catching Backs

Others: Pierre Thomas, Darren Sproles, Roy Helu.

You’ll notice straight away that this group of running backs tends to be extremely efficient on the ground, despite being largely defined by their notable pass-catching skills. Danny Woodhead is the only older player in the database with a rushing distribution almost as impressive as Jamaal Charles.

“The primary difference is usage. __When he’s healthy, Charles is going to receive between 50% and 80% of the running back load during a season. In contrast, Danny Woodhead only receives 20-30% of a team’s carries.__”

“The primary difference is usage. __When he’s healthy, Charles is going to receive between 50% and 80% of the running back load during a season. In contrast, Danny Woodhead only receives 20-30% of a team’s carries.__”

So if these guys are so effective on the ground, then why don’t teams utilize them in the running game more? Why isn’t Woodhead used as much as Charles?

In essence, it’s because these guys are effective on the ground because of the relatively low usage. They’re at their most effective on balanced offenses in situations where a run and a pass are equally likely. They keep defenses guessing, and often benefit from softer fronts than 2-down backs. The dual threat offered by these types of running backs tends to keep defenses honest. Less predictable offenses are harder to defend against, and can be more effective.

“A good quarterback can really keep an offense humming with a talented pass-catching back. Brees and Brady have, in part, built their careers by exploiting the utility that these backs provide in keeping defenses off-balance. It’s no mistake that the primary examples of this archetype include Woodhead, Vereen, Sproles, and Pierre Thomas.”

“A good quarterback can really keep an offense humming with a talented pass-catching back. Brees and Brady have, in part, built their careers by exploiting the utility that these backs provide in keeping defenses off-balance. It’s no mistake that the primary examples of this archetype include Woodhead, Vereen, Sproles, and Pierre Thomas.”

I agree. These sorts of running backs are really easy to under-value because of their relatively low rushing volume. While they can’t thrive as a primary back, they can be a devastatingly effective part of a platoon. For all the speculation that the Dallas run game got this past preseason after Murray went to the Eagles, it was Lance Dunbar who looked like the most effective running back on the team. Why? He could also catch. He was more effective on the ground than the other guys, because defenses had to play him honest.

Looking at these players around the league, it’s mystifying to me that Oakland continually rosters guys like Reece and now Helu without ever really using them correctly. I just don’t get it.

In any case, I hope you’ve found this exploration of running back archetypes interesting. But before we end: Bernie, how do the younger guys look? Are there any first- or second-year players that have really stood out to you so far that you’d like to mention?

“Well, this is a tough question. We don’t know at this point whether particular aspects of a run distribution are actually predictive or not, or how stable exactly the distribution is across time. The rookies that I’d personally want most on my team – like Gurley – aren’t necessarily the ones that have run the most impressively so far. The offensive line and quarterback really do matter a lot, and Gurley has neither on his side. Not to mention the fact that these young guys all have small sample sizes. I really couldn’t tell you who will be a super star later.”

“Well, this is a tough question. We don’t know at this point whether particular aspects of a run distribution are actually predictive or not, or how stable exactly the distribution is across time. The rookies that I’d personally want most on my team – like Gurley – aren’t necessarily the ones that have run the most impressively so far. The offensive line and quarterback really do matter a lot, and Gurley has neither on his side. Not to mention the fact that these young guys all have small sample sizes. I really couldn’t tell you who will be a super star later.”

That’s fine. So let’s be more precise in our question. Retrospectively, who of the young players have been running most like these archetypes so far?

“Fair enough. Rawls and Karlos Williams look like the potential game-breaking talents, with David Johnson and Jerick McKinnon just behind. Carlos Hyde, Lorenzo Taliaferro, Jeremy Hill, T. J. Yeldon, Tevin Coleman, Charcandrick West, and Todd Gurley are the Grinders. If they pan out, that’s a lot of quality starters for teams that have come into the league in the past two years. I see Devonta Freeman as a mediocre home run hitter – nobody else really stands out there. Bishop Sankey is the short-yardage bruiser. David Cobb and Andre Williams look like JAGs, along with maybe Jay Ajayi, Matt Jones, Cameron Artis-Payne, and Melvin Gordon too. Abdullah is the most promising of the pass-catching guys – Sims and Langford haven’t shown me enough in the first few yards yet, and our own James White can’t seem to break into the open field with the ball in his hands.”

“Fair enough. Rawls and Karlos Williams look like the potential game-breaking talents, with David Johnson and Jerick McKinnon just behind. Carlos Hyde, Lorenzo Taliaferro, Jeremy Hill, T. J. Yeldon, Tevin Coleman, Charcandrick West, and Todd Gurley are the Grinders. If they pan out, that’s a lot of quality starters for teams that have come into the league in the past two years. I see Devonta Freeman as a mediocre home run hitter – nobody else really stands out there. Bishop Sankey is the short-yardage bruiser. David Cobb and Andre Williams look like JAGs, along with maybe Jay Ajayi, Matt Jones, Cameron Artis-Payne, and Melvin Gordon too. Abdullah is the most promising of the pass-catching guys – Sims and Langford haven’t shown me enough in the first few yards yet, and our own James White can’t seem to break into the open field with the ball in his hands.”

Thanks Bernie. Rather than post a million more pictures, I’ll just direct you towards our “app”, where you can check out the run distributions for every running backs of the past six years. That’s “app” in quotes because it’s basically just a small visualization script that runs out of an R plugin. Just pop over to the instructions HERE and have fun.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

- 20% of all RB runs in the NFL over the past six years are attributable to just ten players: Gore, McCoy, Lynch, CJ2K, Peterson, Forte, Foster, Steven Jackson, DeMarco Murray, and Morris.

- Half of all active running backs over this 6-year period accumulated fewer than 60 total attempts. A quarter of all running backs since 2010 never made it past 15 total carries. -The run distributions reveal different running styles. We’ve identified six “archetypes”: High-volume Grinders, Home Run Hitters, Short-Yardage Bruisers, JAGS, Elite Pass-Catching backs, and Game-Breaking Talents.

- Grinders include Gore, Morris, Ingram, MJD, Blount, and Lacy. Their value lies in maintaining a high usage rate without sacrificing efficiency in any part of the game.

- Home Run Hitters include McCoy, Peterson, Forsett, Reggie Bush, and Christine Michael. Their value lies in tremendous open-field running that can kick-start a scoring drive.

- Short-Yardage Bruisers include John Kuhn, Shonn Greene, Peyton Hillis, Daniel Thomas, and Law Firm. Their value lies in hitting the line hard and falling forward, reliably picking up at least a yard or two before going down.

- JAGS have value mostly as depth. Most running backs on NFL rosters are JAGs or worse.

- Elite Pass-Catching backs include Woodhead, Pierre Thomas, Sproles, Vereen, and Helu. Their value lies in their versatility, their ability to keep defenses honest as a dual threat, and their ability to exploit soft fronts.

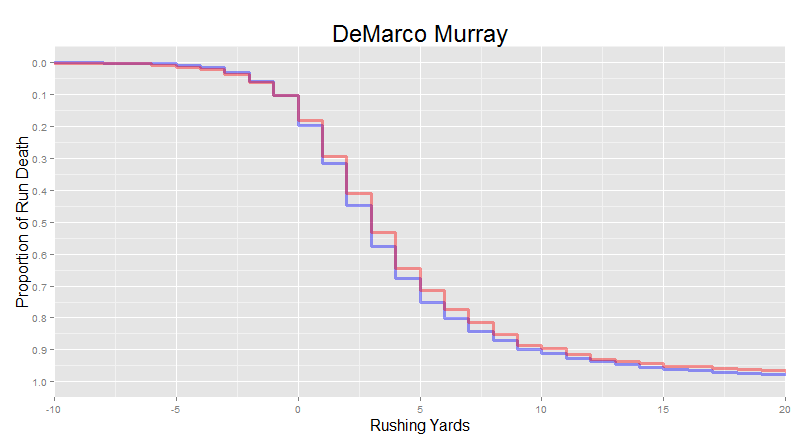

- Game-Breaking Talents include DeMarco Murray, Le’Veon Bell, LaDainian Tomlinson, and Jamaal Charles. They are good at all phases of the run even at a high volume.

- Jamaal Charles looks like the greatest running back of the decade.

- Run distributions are not known to be predictive, but Rawls, Karlos Williams, Jerick McKinnon, and David Johnson are looking very promising.

- 2008 sucked for the Pats.